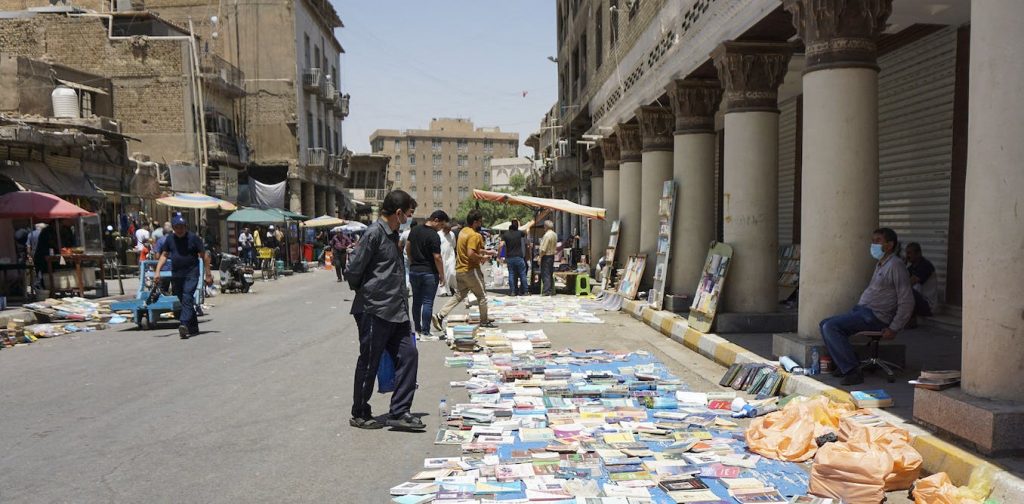

The invasion of Iraq defined US’ foreign relations – but in popular Iraqi literature, the war is just a piece of the country’s complex history

It’s been just over 20 years since the United States invaded Iraq. Some Americans have largely forgotten about the invasion, despite the fact the Sept. 11 attacks that precipitated it still loom large in U.S. national memory. Even during the heart of the war in 2006, most young Americans could not find Iraq on a map.

Many Iraqis, though, have a more nuanced, deeper understanding of the country’s recent history: An understanding which can be seen in their literature – and particularly in the contemporary, post-invasion literature that scholars like me study.

For the past two decades, Iraqi literature in particular has undertaken a deep excavation of its recent past, going far beyond the confines of the U.S. invasion.

Iraqi literature sometimes reflects on the dictatorship of Saddam Hussein, the Iran-Iraq war in the 1980s, and the experience of immigration to Western countries – in addition to 9/11 and the United States’ 2003 invasion of Iraq following false claims of Saddam’s possessing weapons of mass destruction.

In other words, while many in the U.S. have focused on Iraq through the lens of the 2003 invasion, these events are not the heart of contemporary Iraqi literature.

The Iraqi writer Hassan Blasim appears at a book event in 2015. Niklas Maupoix/Flickr, CC BY

The Iraqi writer Hassan Blasim appears at a book event in 2015. Niklas Maupoix/Flickr, CC BY

Literary timelines of Iraqi history

The short stories of Hassan Blasim and Diaa Jubaili, two modern Iraqi storytellers who have both found critical acclaim in Western media, offer a way to understand some of the literary narratives of recent Iraqi history.

Blasim, a filmmaker and writer born in Baghdad in 1973, currently lives in Finland. Jubaili, born in 1977 in Basra near the borders with Kuwait and Iran, has remained in Basra.

Their stories present the U.S. invasion and its consequences as part of a longer history of foreign occupations and internal political violence in Iraq.

This history of violence, their fiction suggests, has roots in the mid-20th century. During that time, newly independent Iraq’s successive governments, and their foreign backers, attempted to chart a path forward for the country.

Blasim and Jubaili show that it is the intervening decades, as opposed to just the U.S. invasion in 2003, that have come to define modern Iraq.

In fact, several of their short stories are written about Iraq’s previous wars and the dictatorship of Saddam, with no reference to the U.S. invasion. When their stories do reference the invasion, it is often as one of a litany of violent events.

Somewhat improbably, many of their stories creatively retell a broad swath of Iraqi history in just a few short pages – an undertaking that might make a historian or political scientist break out in hives.

How could one possibly reduce such complexity to a few pages?

To quote Jubaili: “There is no need to write a story with a lot of words when the idea behind it can only sustain a few lines.”

Simple ideas

Jubaili’s themes – entailing the disorientation caused by cyclical wars – – seem to be summed up in a single line in one of his stories, “The Frog.”

In this story, an enterprising man realizes he will turn a large profit selling frogs that he catches in Basra’s Shatt al-Arab river to East Asian oil refinery workers. One day, he catches a “giant frogman” who has been living in the river since the Iran-Iraq war in the 1980s. Disoriented, the frogman panics, asking the frog catcher: “Is the war over?”

Which war, indeed? By virtue of its geographic position, Basra was at the epicenter of the eight-year war between Iraq and Iran in the 1980s.

But Iraq also experienced political revolutions in 1991, during which armed Kurdish and Shiite minorities attempted to depose Saddam. Iraq also invaded Kuwait in 1990 because of territorial ambitions. This led the United Nations to issue crippling economic sanctions for the next 13 years.

Like the frogman, the lives of Jubaili’s characters are marked by many of these events.

The Iraqi author Diaa Jubaili is an example of a writer from the country who mentions, but does not focus excessively on, the U.S. invasion. Diaa1977/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

The Iraqi author Diaa Jubaili is an example of a writer from the country who mentions, but does not focus excessively on, the U.S. invasion. Diaa1977/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

A closer read

Where Jubaili’s stories are often absurd and vaguely humorous, Blasim’s prize-winning short stories are hard to read. His prose unflinchingly describes all manners of violence and human suffering.

In the 2014 short story “The Hole,” a man fleeing masked gunmen in Baghdad trips and falls into a deep pit. Quickly, he realizes that he is not the only person trapped there. There is another man: someone who claims to be a jinn – or genie – who fell in while fleeing persecutors during the Abbasid Caliphate, which ruled the area that is now Iraq from 750 to 1500 C.E. Also sharing the hole is the corpse of a Russian soldier from the Soviet-Finnish war, waged from 1939 to 1940.

After a few pages, a woman covered in electronics fleeing a dystopic, futuristic robot falls into the hole, as well. The hole becomes a metaphor for a chain that links “bloody fights, repetitive and disgusting” across time and space, according to the story.

History, it seems, acts as “a photocopier churning out copies” upon which are imprinted “the same face, a face shaped by pain and torment,” as Blasim writes.

In another of Blasim’s short stories, “The Madman of Freedom Square,” a man considered insane by the people of his town narrates three generations of his family history against the backdrop of the ebbs and flows of competing 20th-century political and religious ideologies.

In the story’s final lines, set in the present day, a stranger talks the unwitting narrator, “the madman of Freedom Square,” into wearing an explosives-strapped vest.

Ultimately, these stories encourage readers to elevate the importance of human lives over the events that are said to define them.

This literature resists narratives of the U.S. invasion as a supposedly exceptional event. It also resists the tokenized testimonies of the survivors of the occupation: those faces that are the usual focus of media coverage, academic scholarship and political punditry in the U.S.

And even in the stories’ insistence on the ever-presence of death, whether in Blasim’s macabre and violent tones or in Jubaili’s sometimes-humorous, sometimes-absurd ones, this literature becomes a metaphor for the immense fortitude that it takes to survive and give meaning to one’s world.