How book-banning campaigns have changed the lives and education of librarians – they now need to learn how to plan for safety and legally protect themselves

Despite misconceptions and stereotypes – ranging from what librarians Gretchen Keer and Andrew Carlos have described as the “middle-aged, bun-wearing, comfortably shod, shushing librarian” to the “sexy librarian … and the hipster or tattooed librarian” – library professionals are more than book jockeys, and they do more than read at story time.

They are experts in classification, pedagogy, data science, social media, disinformation, health sciences, music, art, media literacy and, yes, storytelling.

And right now, librarians are taking on an old role. They are defending the rights of readers and writers in the battles raging across the U.S. over censorship, book challenges and book bans.

Book challenges are an attempt to remove a title from circulation, and bans mean the actual removal of a book from library shelves. The current spate of bans and challenges is the most notable and intense since the McCarthy era, when censorship campaigns during that Cold War period of political repression included public book burnings.

But these battles are not new; book banning can be traced back to 1637 in the U.S., when the Puritans banned a book by Massachusetts Bay colonist William Pynchon they saw as heretical.

As long as there have been book challenges, there have been those who defend intellectual freedom and the right to read freely. Librarians and library workers have long been crucial players in the defense of books and ideas. At the 2023 annual American Library Association Conference, scholar Ibram X. Kendi praised library professionals and reminded them that “if you’re fighting book bans, if you’re fighting against censorship, then you are a freedom fighter.”

Library professionals maintain that books are what education scholar Rudine Sims Bishop called the “mirrors, windows and sliding glass doors” that allow readers to learn about themselves and others and gain empathy for those who are different from them.

The drive to challenge, ban or censor books has not only changed the lives of librarians across the nation. It’s also changing the way librarians are now educated to enter the profession. As a library school educator, I hear the anecdotes, questions and concerns from library workers who are on the front lines of the current fight and are not sure how to react or respond.

What once, and still is, a curriculum that includes book selection, program planning and serving diverse communities in the classroom, my faculty colleagues and I are now expanding to include discussions and resources on how students, once they become professional librarians, can physically, legally and financially protect themselves and their organizations.

Demonstrators who support banning books gather during a protest outside of the Henry Ford Centennial Library in Dearborn, Mich., on Sept. 25, 2022. JEFF KOWALSKY/AFP via Getty Images

Demonstrators who support banning books gather during a protest outside of the Henry Ford Centennial Library in Dearborn, Mich., on Sept. 25, 2022. JEFF KOWALSKY/AFP via Getty Images

More than shelving books

Degreed librarians are professionals with master’s degrees from nationally accredited academic programs. I have personally gone through such a program and now teach in one.

In fact, many librarians who work on college and university campuses have subject masters and doctorates, and K-12 librarians must have a valid teaching license or a state endorsement to work in a school library or media center. They know how to select appropriate materials for communities.

Librarians adhere to core values, standards and professional ethics. They see it as their duty to create and maintain a collection that reflects the diverse needs and interests of the entire community, not just for a select, vocal part of the community. The Freedom to Read statement of the American Library Association tells us: “It is the responsibility of publishers and librarians, as guardians of the people’s freedom to read, to contest encroachments upon that freedom by individuals or groups seeking to impose their own standards or tastes upon the community at large; and by the government whenever it seeks to reduce or deny public access to public information.”

Books are challenged and banned for many reasons, including profanity, depictions of sex, LGBTQIA+ content, depictions of sexual abuse, equity, diversity and inclusion content, depictions of drug use and alcoholism, anti-police rhetoric and providing sex education. Reasons for challenges can be personally subjective, and claims that books present divisive topics that should be excluded from collections are increasing.

George Johnson, author of the frequently banned book “All Boys aren’t Blue,” has said that he believes books are challenged to eliminate narratives that elucidate the truths of marginalized groups and depict the everyday diversity of their lives. Johnson believes the stories of the LGBTQIA+ and minoritized communities are specifically under attack.

Johnson is a complainant in a recently filed federal lawsuit against Florida’s Escambia County School District and School Board, which unanimously voted to remove Johnson’s book from their school libraries because of passages that describe a sexual experience.

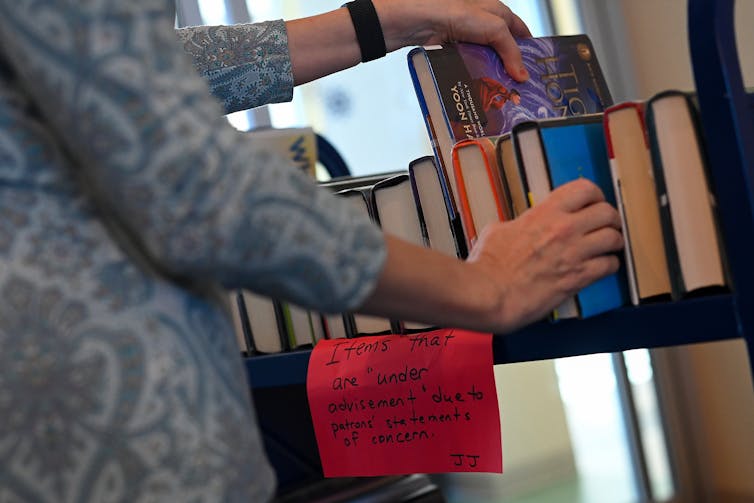

St. Tammany Parish Library Director Kelly LaRocca shows off a cart of books that were removed from the shelves at the Peter L. ‘Pete’ Gitz Library on Feb. 13, 2023, in Madisonville, La. Joshua Lott/The Washington Post via Getty Images

St. Tammany Parish Library Director Kelly LaRocca shows off a cart of books that were removed from the shelves at the Peter L. ‘Pete’ Gitz Library on Feb. 13, 2023, in Madisonville, La. Joshua Lott/The Washington Post via Getty Images

The new librarians’ education

To balance the needs of everyone in the community, libraries have collection development policies as well as reconsideration and withdrawal policies that guide librarians in selecting new books and materials and removing those that are outdated. These policies are key when facing potential bans and challenges.

But with the current controversies about racially diverse and LGBTQIA+ books, policies are no longer enough to demonstrate the integrity of professionally curated library collections.

Neither policies nor book reviews nor professional expertise are keeping library workers from being called pedophiles, groomers, indoctrinators and pornographers. They are being harassed, receiving death threats and being fired. Libraries have been sued and library workers are so threatened and harassed that they are getting sick and leaving their careers.

The current threats to librarians and the books they circulate are necessitating a shift in the content of graduate library education. Librarians obviously need to know the content of books. But educators like me now know we need to provide graduate students with information about how to physically and legally protect themselves and their organizations.

When we teach intellectual freedom, we also teach students how to prepare for protesters and contentious board meetings. When we teach information professionals how to select materials for their libraries, we emphasize their need to know how to articulate, in writing, the reasons for having a particular book, film or material item in their collection.

I believe that our students now need to consider getting professional liability insurance in case they are sued for buying a contested book. And when we teach story-time planning, we can pair that with strategies to devise a safety plan in case they are threatened or receive a bomb threat because of their work.

Librarians and the future librarians we teach have always loved books and reading. While our work has changed in this era of increasing censorship, in one sense it has not: We’re still devoted to the idea that we serve our communities by providing them with books that open the world to them and give them the opportunity to learn about themselves and others.